Affiliates Flock to ‘Soulless’ Scam Gambling Machine

Last month, KrebsOnSecurity tracked the sudden emergence of hundreds of polished online gaming and wagering websites that lure people with free credits and eventually abscond with any cryptocurrency funds deposited by players. We’ve since learned that these scam gambling sites have proliferated thanks to a new Russian affiliate program called “Gambler Panel” that bills itself as a “soulless project that is made for profit.”

A machine-translated version of Gambler Panel’s affiliate website.

The scam begins with deceptive ads posted on social media that claim the wagering sites are working in partnership with popular athletes or social media personalities. The ads invariably state that by using a supplied “promo code,” interested players can claim a $2,500 credit on the advertised gaming website.

The gaming sites ask visitors to create a free account to claim their $2,500 credit, which they can use to play any number of extremely polished video games that ask users to bet on each action. However, when users try to cash out any “winnings” the gaming site will reject the request and prompt the user to make a “verification deposit” of cryptocurrency — typically around $100 — before any money can be distributed.

Those who deposit cryptocurrency funds are soon pressed into more wagering and making additional deposits. And — shocker alert — all players eventually lose everything they’ve invested in the platform.

The number of scam gambling or “scambling” sites has skyrocketed in the past month, and now we know why: The sites all pull their gaming content and detailed strategies for fleecing players straight from the playbook created by Gambler Panel, a Russian-language affiliate program that promises affiliates up to 70 percent of the profits.

Gambler Panel’s website gambler-panel[.]com links to a helpful wiki that explains the scam from cradle to grave, offering affiliates advice on how best to entice visitors, keep them gambling, and extract maximum profits from each victim.

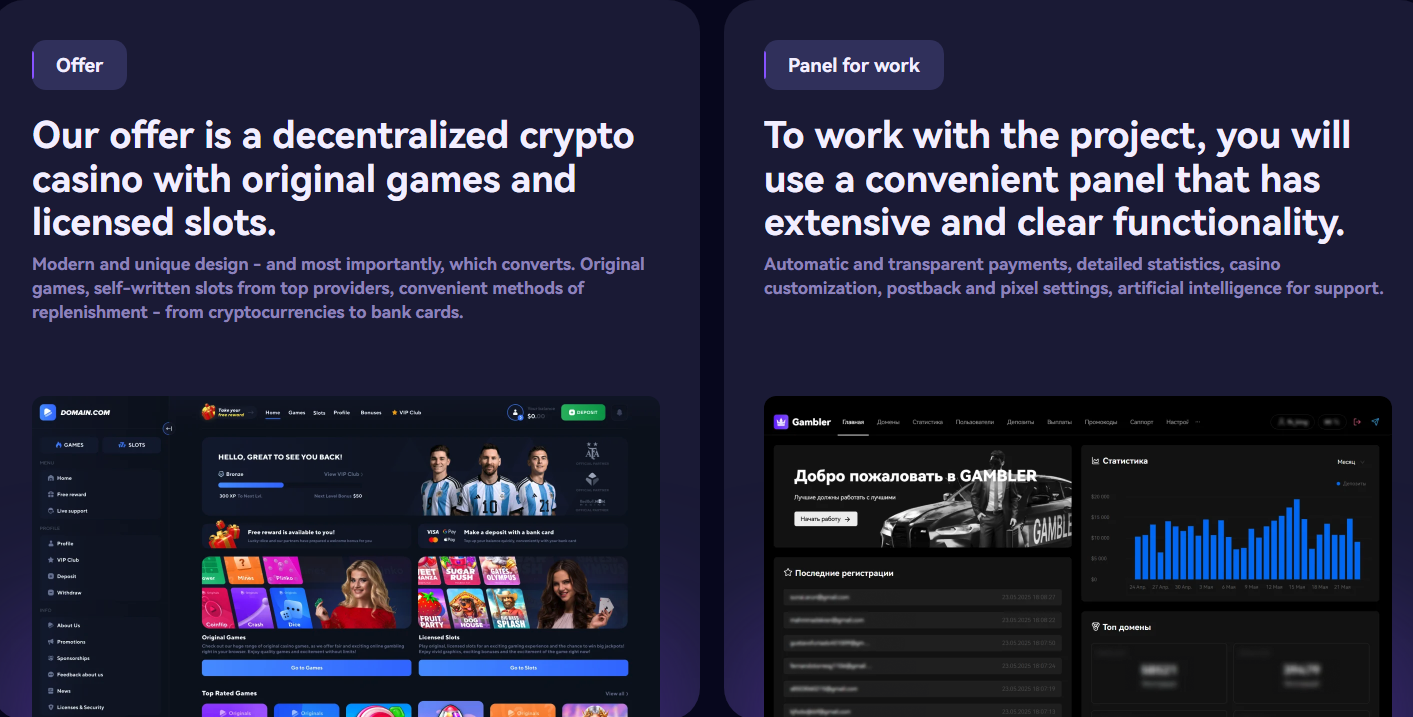

“We have a completely self-written from scratch FAKE CASINO engine that has no competitors,” Gambler Panel’s wiki enthuses. “Carefully thought-out casino design in every pixel, a lot of audits, surveys of real people and test traffic floods were conducted, which allowed us to create something that has no doubts about the legitimacy and trustworthiness even for an inveterate gambling addict with many years of experience.”

Gambler Panel explains that the one and only goal of affiliates is to drive traffic to these scambling sites by any and all means possible.

A machine-translated portion of Gambler Panel’s singular instruction for affiliates: Drive traffic to these scambling sites by any means available.

“Unlike white gambling affiliates, we accept absolutely any type of traffic, regardless of origin, the only limitation is the CIS countries,” the wiki continued, referring to a common prohibition against scamming people in Russia and former Soviet republics in the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The program’s website claims it has more than 20,000 affiliates, who earn a minimum of $10 for each verification deposit. Interested new affiliates must first get approval from the group’s Telegram channel, which currently has around 2,500 active users.

The Gambler Panel channel is replete with images of affiliate panels showing the daily revenue of top affiliates, scantily-clad young women promoting the Gambler logo, and fast cars that top affiliates claimed they bought with their earnings.

The apparent popularity of this scambling niche is a consequence of the program’s ease of use and detailed instructions for successfully reproducing virtually every facet of the scam. Indeed, much of the tutorial focuses on advice and ready-made templates to help even novice affiliates drive traffic via social media websites, particularly on Instagram and TikTok.

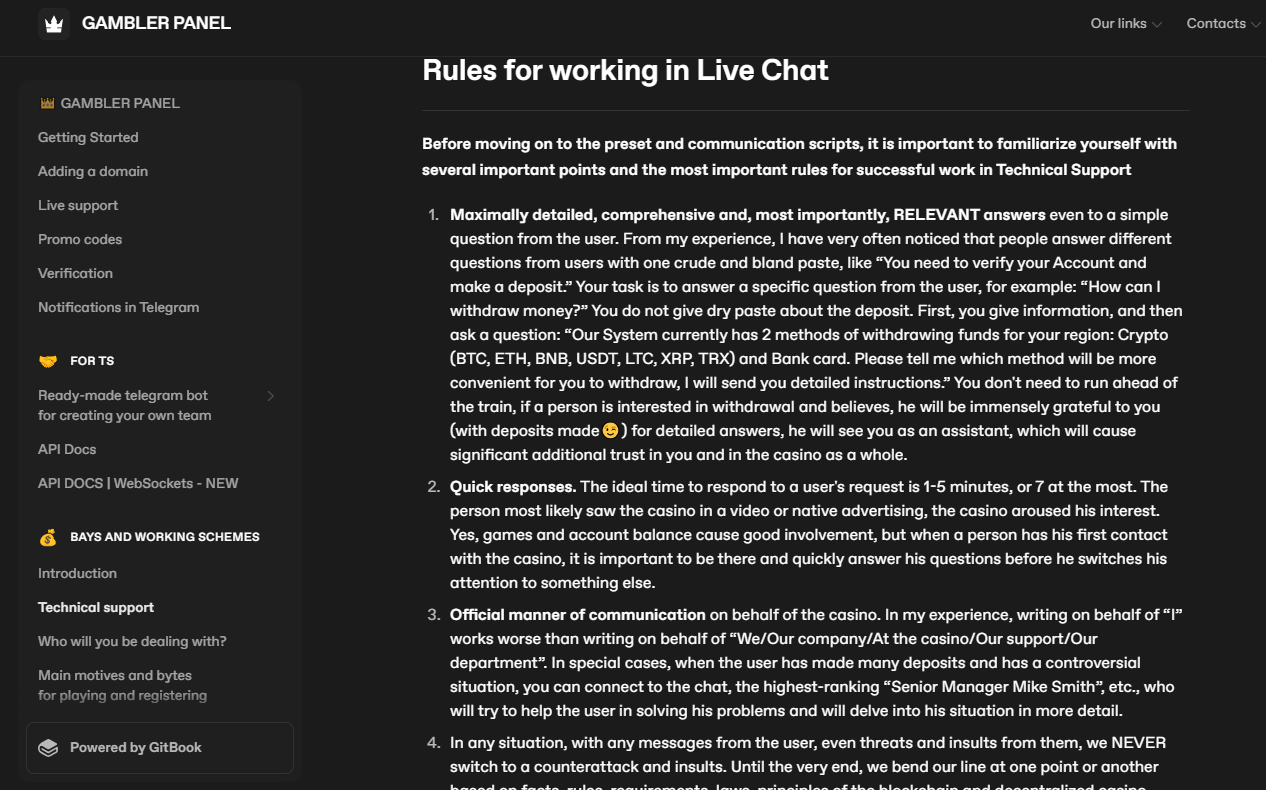

Gambler Panel also walks affiliates through a range of possible responses to questions from users who are trying to withdraw funds from the platform. This section, titled “Rules for working in Live chat,” urges scammers to respond quickly to user requests (1-7 minutes), and includes numerous strategies for keeping the conversation professional and the user on the platform as long as possible.

A machine-translated version of the Gambler Panel’s instructions on managing chat support conversations with users.

The connection between Gambler Panel and the explosion in the number of scambling websites was made by a 17-year-old developer who operates multiple Discord servers that have been flooded lately with misleading ads for these sites.

The researcher, who asked to be identified only by the nickname “Thereallo,” said Gambler Panel has built a scalable business product for other criminals.

“The wiki is kinda like a ‘how to scam 101’ for criminals written with the clarity you would expect from a legitimate company,” Thereallo said. “It’s clean, has step by step guides, and treats their scam platform like a real product. You could swap out the content, and it could be any documentation for startups.”

“They’ve minimized their own risk — spreading the links on Discord / Facebook / YT Shorts, etc. — and outsourced it to a hungry affiliate network, just like a franchise,” Thereallo wrote in response to questions.

“A centralized platform that can serve over 1,200 domains with a shared user base, IP tracking, and a custom API is not at all a trivial thing to build,” Thereallo said. “It’s a scalable system designed to be a resilient foundation for thousands of disposable scam sites.”

The security firm Silent Push has compiled a list of the latest domains associated with the Gambler Panel, available here (.csv).